Present at the Dissolution

On Teaching the History of Western Art For the Very Last Time

Last February my department sent me and my fellow art history grad students an email about a job opening at a public university in the northeast. The email started like this:

The Department of Art and Art History invites applications for a full-time, non-tenure track Lecturer position in Art History for the Academic Year 2022-23, with intent for renewal pending satisfactory performance. We seek candidates with expertise in American Art of the 18th-20th centuries, or Visual Studies, with the ability to teach an introductory survey course (Renaissance to Contemporary), and intermediate and advanced courses in their area of expertise. A successful candidate will demonstrate a commitment to problematizing and dismantling the canon and its roots in white supremacy, and have the ability to teach about artists and makers who have been historically marginalized.

At the time I was two months away from defending my dissertation. The specialty was off, but otherwise it was the sort of job I might hope to get. If the same school sends out a similarly-worded email next February, but for someone who knows about seventeenth-century Europe, I’ll apply.

Not that I’m committed to problematizing and dismantling the canon and its roots in white supremacy. On the contrary, I got into art history because I liked canonical art and wanted to learn more about it. After spending the second half of my twenties in Eastern Europe, teaching English and updating travel guides, I spent most of my thirties outsourcing financial presentations at an investment bank in lower Manhattan. I was good at that job, and it was satisfying in some ways, but I had no interest in promotions, and always knew I’d leave when I could. In 2013, after about eight years, I finally found myself in a position to do something else. I chose to go back to school for art history because I thought it might suit me to work in a museum.

I was right and wrong. Art history suited me, and I haven’t looked back, but when I got an internship working on an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art I found that I felt out of place behind the scenes there. While I’m grateful to have had the experience, I now know I’m better off in a classroom than a curatorial department.

So here I am, in my late forties, fully credentialed. I suppose that means I’m equipped to play my part in the endeavor to problematize and dismantle the canon. Let me try for a paragraph or two to take this seriously.

Roots in white supremacy? Giorgio Vasari was famously a Florentine supremacist, and it’s true that when the French art critic Roger de Piles published his balance de peintres in 1708, he ranked Raphael and Rubens highest and failed to include a single non-European. But how could he have known about any? I suppose the department that posted the ad would like to banish or at least demote the likes of Vasari and Roger de Piles, not on the grounds that those two were themselves white supremacists, but because centering the European history of art history is privileging whiteness, in the same way that the Metropolitan Museum can be said to center whiteness by placing its old European paintings up the main stairs from the entrance. Privileging—I dislike ‘privilege’ as a verb, but the argument that it makes less sense to privilege Vasari in a 60% white country (as the United States is today, if you don’t count Hispanics) than it did in an 80% white country (as the United States was in 1980) is a reasonable one. Six decades on from the Hart-Celler Act, I see the case for a different approach. But from there to avowing roots in white supremacy—to me it’s an implausible leap. Whatever it was that enabled Europeans to dominate the globe for half a millenium, it wasn’t their admiration for ancient marble statues.

As for dismantling the canon, if you suppose canon to mean something like, the work of those artists who are held in general esteem at a given moment, well, that changes over time.1 There are only a handful of painters who have never been out of style in the West; others come and go and come again. But could the concept itself be dismantled? If the Metropolitan Museum sold its Bruegel, would that amount to a dismantling? No, because it would fetch a quarter of a billion dollars.2 It would only be a dispersal. Even the destruction of the work wouldn’t do the trick. It didn’t for the first version of St. Matthew and the Angel, no less important in Caravaggio studies today for having been lost in Berlin in 1945. Problematizing doesn’t seem to be happening, either. The great effort in the last few years on the part of museums to increase their holdings of works by artists not white and male is a shift in taste and priority, but there is no escaping selection, preference and discrimination. There is no going back to anonymous sculptors, masons and manuscript illuminators.3

Regarding my own research, it’s true that my dissertation is Eurocentric, but I’m not invested in the greatness of the artists I wrote about, mostly little-known or anonymous seventeenth-century printmakers. I’m not even sure I like them. It was simply interesting to try to make sense of their work.

This attitude helps me to shrug my shoulders. I’m not that stubborn. My goal now is to work at a college or university, teaching young people about the art of the past. I’m willing to cheat a bit to get there, willing to give an interviewer the wrong impression about ideological commitments I consider nonsensical. And it’s possible I won’t have to. I’m good at setting people at ease, seeming reasonable, and this makes people assume I see the world as they do.

*

As it happened I got my first teaching job without being asked any questions at all. In April, not long before my defense, a department administrator sent out an email asking if anyone wanted to teach over the summer. Knowing that late-stage or just-finished PhD students have priority for summer teaching, I replied right away, and ended up with the assignment to teach the first half of the department’s survey course, covering Western art up to the Gothic era. ‘Western’ is defined loosely, so that the syllabus includes Egyptian, Mesopotamian and Islamic art, but there’s nothing from Asia east of Persia, and Sub-Saharan Africa makes a single, brief appearance, when the Nubian Kingdom of Kush ruled Egypt around 700 BC.

This not being my period, I wasn’t all that familiar with the material. I would have been hard pressed to state in more than vague terms what differentiates Romanesque and Gothic architecture, to identify the features of a mosque, or to do anything more than repeat a few clichés about Greece and Rome.

Which is to say, when I took the assignment in April, I didn’t feel I was going to be that far ahead of the students I was to teach in June. Around the same time I learned something else. For a while my department had been planning to switch the focus of its survey courses from Western Art History to Global Art History, and the new version was to be taught for the first time in the fall.

That sounds like a worthy change. Expose students to more art from a wider variety of cultures by spending less time on Greece and Rome, dropping the Hiberno-Saxon manuscripts, and looking only at one cathedral, and then using the hours gained for classes on Mesoamerica, Buddhism, Chinese landscape painting, and African kingdoms. But the course also changes on an abstract level. The themes of Western art history are influence and development. After the prelude of cave paintings, which belong to prehistory, the cultures are all connected. Sumerians influenced Egyptians, Egyptians influenced Assyrians, Egyptians and Assyrians influenced Greeks, and Greeks influenced Romans. The Romans influenced everyone who followed them, the Byzantines, the Umayyads, the Franks. And all of these cultures influenced, directly or indirectly, the later Europeans. Greek art is presented in a sequence: the Geometric style developed into the Archaic, which led to the Classical and then the Hellenistic. Pompeii wall paintings are divided into stylistic periods. Centuries later, a series of innovations in channeling weight down via buttresses and piers allowed church builders to go higher and higher, and to give more and more wall space to windows.

Much of this is lost in the shift to Global Art History. Instead of influence and development, there are connections. A range of cultures across time and space, not necessarily in communication with each other, but with common practices, materials and techniques. The Egyptians, the early Chinese, and the Mochi of ancient Peru filled the tombs of the powerful with precious objects. The Olmecs, like the early Chinese, contrived in spite of its hardness to sculpt jade. Great cities, the centrality of religion, trade, division of labor—the building blocks of our shared humanity serve just as well for the construction of a survey course as the enduring resonance of the Classical heritage.

I don’t want to get into the question of relative merits; let it suffice to say that the two approaches are different, and that there is plenty to be said in favor of each (and against: at the worst, the old approach is chauvinistic and the new one watery). My subject here is rather that I unexpectedly found myself in the position of being the last one to teach the class the old way. When my students finished their exams on the last day I would be the one to flip the switch on Western civ for good. When the lights came back on in September, Athens and Rome would no longer be at the center of the course, but two cities among many.

*

I started preparing right after defending my dissertation. I had about five weeks before the summer semester began, not enough time to write fourteen three-hour lectures covering thousands of years of art history. Nor was I likely to master the material well enough to speak extemporaneously from slides of images alone. So I used bullet points. Here’s a typical slide, from the eleventh lecture, on Romanesque art.

You only get to teach in your discipline for the first time once. If I manage to keep teaching, in the years to come my confidence and fluency will grow, and I’ll pare down the bullets. My knowledge will deepen, and I’ll have more to say. I might read a book about the furta sacra, or learn something about Roman parade helmets like the one that was used to make the reliquary’s head. But I won’t match the enthusiasm I had this summer. I won’t match the delight I felt when it turned out one student knew the Greek myths well enough from video games and fantasy novels that I could delegate some of the story-telling, could count on the student to explain to the rest of the class what Hercules was up to on this or that vase. And next time I talk about the disappearance of concrete as a building material after the collapse of the Roman Empire, the room may still be filled with students marveling that something as simple and essential as concrete could fall out of use, but I won’t also be marveling at their marveling, because now I’ve seen it.

My students weren’t aware they were taking the class the last time it would be offered. If I hadn’t mentioned it, I’m not even sure they would have realized they were enrolled in Western rather than Global Art History. Two-thirds of undergraduates at my school are not white, but I never got the impression they yearn for an approach more aligned with their demographics. I was curious about this, though, so to find out what interested them most I asked them on the midterm.

The answer, by a margin strong enough to break a filibuster, was Greece. My students wanted more myths, more sculpture, more vases. It occurs to me now, as I write these words, that I failed to bring in the Ode on a Grecian Urn. Oh, well. At least I had the sense when we got to Rome to include the dying gladiator stanzas from Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage.

I touched on the present here and there, where there were contemporary resonances, but always lightly, and never for long. When I showed my students this slide, for example, in the context of Byzantine iconoclasm, I told them that I had only one comment to make about iconoclasm in our own times. “If you ever find yourself involved in one of these situations, watch where you’re standing. These suckers are heavy.” They all laughed (and, I hope, took the point), and we went back to the ninth century.

I also spoke about the afterlives of objects. The Laocoön, dug up in Rome in 1506 in the presence of Michelangelo, recognized immediately thanks to its description by Pliny the Elder, and in 1610 the inspiration for an El Greco painting now in Washington. Roman ruins used for centuries as quarries for new buildings, for shepherds to rest their flocks, as sites for squatters to set up modest dwellings. The Parthenon, converted to a church, then a mosque, and then damaged in 1687 because the Ottomans stored gunpowder in it during a war with Venice; Lord Elgin’s acquisition of most of the surviving sculptures in 1801, his sale of them to the British Museum in 1816, and the formal request made by the Greek government for their return in 1983.

I didn’t weigh in with an opinion on the Greek request. I only noted that the sale took place in Ottoman times, when there was no Greek state. And I added that, more generally, this is a principle museums use to justify holding on to objects acquired in the distant past—other times, other customs, of course, but also, other times, other countries.

I’m there to explain the controversy, give my students the chance to muse over it if they want to, and then to return to the works. In the context of a survey class in the United States it is of no consequence whether the label on the PowerPoint slide says London or Athens.4

*

When the class ended in late July I returned to my dissertation, which though I had defended it April still needed a week or two of polishing before I could hand it in for a diploma. What a comedown, after the pyramids, the temples, and the cathedrals, to go back to writing and rewriting judicious sentences about seventeenth century prints. It felt like a party had ended.

I had joked that a funny thing about art history is that the most prestigious thing you can do closely resembles the least prestigious thing you can do. By this I meant that teaching a survey class isn’t very different from presenting the history of art to the masses who watch PBS or the BBC. What I said wasn’t strictly accurate, as there are more prestigious things than going on television, but the larger point is true. In both cases you have a non-specialist audience that, at least in theory, is curious about objects that have survived through the centuries. Your job is to choose the objects and say something interesting about them. Setting aside the disparities in status and pay, each format has its advantages. Doing a documentary, you get to stand in front of the work, or perhaps on the streets of city where it was made, you can do multiple takes, you can add a soundtrack for extra drama. But in the classroom you see your audience. You can ask them questions, judge their engagement, linger on the objects that catch the attention, start a discussion, announce a fifteen-minute break.

I’m not sure how my career in art history will go from here, where my eccentric decision to get a PhD in my forties will take me. The next step is to publish an article or two from my dissertation and try to get a postdoc. Beyond that, the chance of my ever getting tenure somewhere is vanishingly small. That’s fine. I’ll be satisfied if I can keep teaching.

*

I’ve never read Present at the Creation, Dean Acheson’s memoir of the State Department in the early years of the Cold War, but I’ve always thought it had a good title, one that expresses well the position of an insider at a time when a new era is taking shape.

I’ll be teaching the new Global survey course this spring. I’m looking forward to it. By the time the semester ends in May I’ll know more about South Asian, East Asian, African and pre-Columbian art than I do now. But I’m also grateful to have done it the old way once, to have been present at the last moment before the dissolution.

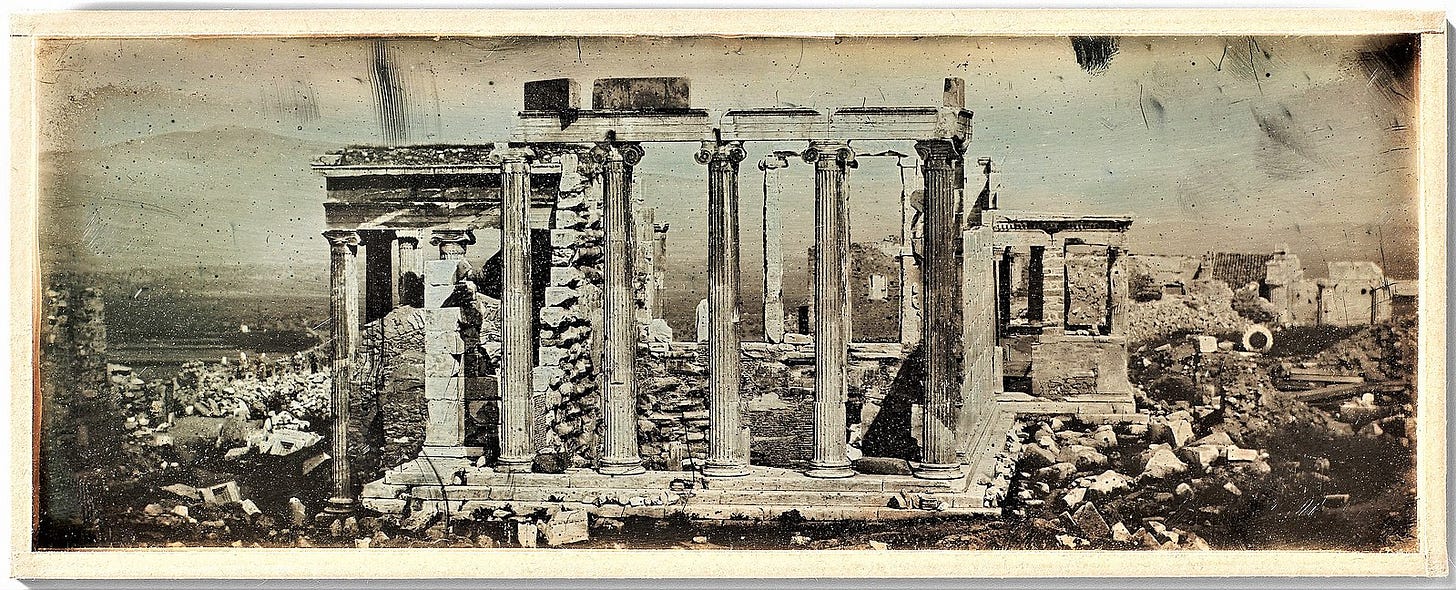

[Title image: Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey, Erechtheion, Athens, 1842, Daguerreotype. Metropolitan Museum of Art]

My favorite book on this subject is Francis Haskell’s Rediscoveries in Art: Some Aspects of Taste, Fashion, and Collecting in England and France.

In 2013 Christie’s estimated the Bruegel at the Detroit Museum of Art, The Wedding Dance, would sell for $100 to $200 million. PDF of Christie’s report to the Office of the Emergency Manager

The exhibition Hear Me Now: the Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina, at the Metropolitan Museum through February 5 (and at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston from March 4 to July 9), is a good example. It is organized around the work of the enslaved poet and potter David Drake, who wrote verses on the large, stoneware jugs he made in antebellum South Carolina. Go see it if you can.

In the event the twenty-first century news item that most interested my students was not the dispute over the ownership of the Parthenon sculptures, but the status of the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. They were unanimously in favor of Turkish President Recep Erdogan’s decision to convert it from a museum back to a mosque.

I enjoyed reading this so much. Your students are very lucky.

This thing called "Leftism" (whether of the Marxist or Social Justice variety) pronounced a death sentence against European civilization and capitalist liberal democracy over a century ago and has worked nonstop to put it into effect, and now that it has entered into an marriage of convenience with global capitalism it is (ironically?) about to achieve its goal.

The reasons why Western Civ had to die have shifted depending upon time and place, first it was because of the crimes of the capitalists against the "proletariat", then once the working class raised its standard of living it became about escaping traditional conformity and achieving a post-Freudian sexual/spiritual liberation, and lastly the reason is Bigotry, or the crimes of Europeans against women, blacks/browns & gays.

Either way, the reasons shifted but the leaders were always the same: secular mostly non-creative intellectuals who imagine themselves a tribe of enlightened philosopher-kings who promised "socialist liberation" and a ticket to the Promised Land if only we gave them unlimited power.

At a certain point post-60s the New Leftists decided that their best hope of fulfilling their power fantasies was invading and conquering the Academy and gradually converting people to their belief system, one student at a time. They styled themselves as "official defenders of the Oppressed" which allowed them to seize the moral high ground and smear any opponents with all sorts of promiscuous bigotry accusations.

And now their victory is complete: young scholars only choose a specialty so they can denounce and demolish it, and there are very few works of art, thought or scholarship that are not infused with their propaganda.

The only consolation is that these termites of civilization can only destroy, not build. Art, art history and scholarship thrived and survived before American academia existed, and will do so once again after American academia commits suicide.