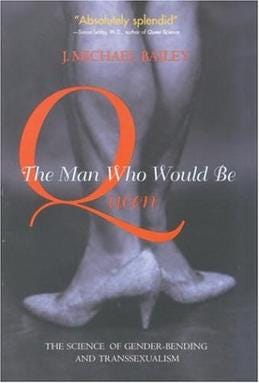

There's a striking passage early in Michael Bailey's nonfictional chronicle of feminine boys and men, The Man Who Would Be Queen, the Science of Gender Bending and Transsexualism, in which the author muses about a world transformed on behalf of the subjects of his scholarly inquiry and of his book.

"Imagine that we could create a world in which very feminine boys were not persecuted by other children and their parents allowed them to play however they wanted," he proposes.

Bailey asks only that we imagine such a world and does not say how it could come into being. In the absence of even a speculative account of how we could get there, presumably through some kind of systematic re-engineering of attitudes begun at the earliest age that was not conceivable in 2003, the scenario remains a fantastical thought experiment by design.

The limit to the author's imagination -- both how far it reached and where it could not ultimately go -- is key to what would befall him upon the publication of his book. As with many works situated on the other side of the yawning chasm separating our post-Awokened age from the Before Times, much of the interest in revisiting the 2003 book today is in seeing what the antediluvian mind that wrote it could and could not anticipate in advance of the flood that the book would itself have a role in summoning.

The opening chapter of the book recounts the story of a boy named Danny, who emerges from his mother's closet at the age of one with a pair of strappy heels. His interest in dressing like a girl never abates and expands into an exclusive interest in playing with girl's toys. Though his sister forbids him to keep stealing his dolls, and his father "furiously snatches" a Barbie doll given to him by his female babysitter away, his mother persuades her husband that it is "only a phase." But by his fifth year, two older boys move down the street and call him a sissy and a fag. ("When she defined a “fag” to Danny as “a boy who loves other boys,” Danny protested, “But I don’t even like boys!”) Later, Danny befriends a boy and spends a night over at his house. But the boy's father forbids that the two continue playing with each other after witnessing the two play house, with Danny in the role of the wife.

In addition to portraying a social world hostile to Danny's gender nonconformity, Bailey describes a psychiatric profession inclined to diagnose his condition in terms that he invites the reader to regard as backward.

"After a couple of months of therapy, a psychiatrist explained that Danny’s feminine behavior was a direct consequence of her being unavailable to him during his first year-that because she was an absent mother, Danny had reconstructed a substitute woman in himself. Although he did not say so outright, it was clear that the psychiatrist believed that Danny’s atypical behavior was all her fault."

A school psychologist with whom she seeks a second opinion sternly reprimands her:

"Giving Danny Barbies and letting him cross-dress were “inappropriate parenting behavior,” she said. Danny’s parents had been “neither willing nor able to set reasonable limits” on his feminine strivings, the report continued. The psychologist advised that if immediate steps were not taken, Danny faced social ostracism and would probably develop “a homosexual preference.”

Bailey is describing a facet of the world for which a term had not yet been coined at the time of its writing. Through the vehicle of one boy’s life, he provides a vivid demonstration of what the activist-oriented of today would call the “cisheteronormative” bias endemic to Western societies, a bias deeply woven into the fabric of everyday life, engineered into the very language we speak, pervading the scientific and medical discourses through which we become subjects of formalized knowledge. It is a part of a vast socialization process that accounts for why an 8-year old boy who moved in down the block already knew to call Danny a fairy and a fag, and indeed the same process that caused his school psychologist to portray “a homosexual preference” as a threatening prospect that could yet be averted by ceasing to indulge his feminine desires.

Danny’s story awakens sympathy of a purely personal kind. He is still yet the isolated sufferer of a very rare and esoteric psychiatric condition, of interest to clinicians like the ones at the center of Bailey’s book — men like Bailey himself, Ray Blanchard, and Ken Zucker. These once dominant figures in the field of transsexualism share in common a touristic fascination with the outer extremity of human variation that has drawn them to this subject, but also a real tenderness for the feminine men that they study. But they do not think of them either as causes for the remaking of the world or as instruments through which that remaking can be effected.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Year Zero to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.