The Glass Delusion and Transgenderism:

Or, what it means to be human in the Renaissance and the twenty-first century

Today’s guest post by a pseudonymous history professor teaching somewhere in the United States, draws a parallel between a delusion spread through social contagion from the 15th to the 17th century in Europe borne aloft by new communications technology, and a new one spreading today on the wings of new communication technology - a novel way of being entirely dependent on synthetic hormones, cosmetic surgery, and the Internet.

by Aphra Behntham

Reports of the secularization of our society have been greatly exaggerated. We moderns of the WEIRD world (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) enjoy pointing to the social contagions of the past and congratulating ourselves on how far humanity has come since witch hunts, trepanation, lynchings, lobotomies, or other barbaric treatments for social or personal afflictions ran riot. But those of us who live in the modern West are still living in an enchanted world.

Transgenderism is an utterly novel concept that has spread via social media to become the first Internet-enabled social contagion. Many are wondering why this factitious idea—the notion that men can literally be women, or that women can literally be men, or that any child could ever be “born in the wrong body”—has spread so far and penetrated the modern West so quickly. This is because transgenderism has attached itself to heroic progressive causes like the Black and Chicano Civil Rights movements, Red Power, women’s rights, and gay rights, portraying itself like the natural successor to these heroic movements. Progressive Americans are hard-wired to accept rights claims as revealed truth and to see “the moral arc of the universe bend[ing] towards justice” as time’s arrow, the clear logic of history. The American Left has been in search of a new oppressed identity category to liberate since the stunning victory of the gay rights movement with the Obergefell decision in 2015.

In the U.S., all civil rights movements engage in a search to find themselves history, and to portray their victory as a part of the heroic American story of the expansion of life, liberty, and justice to include us all. Activists engage in this rewriting of history to include them, and then after their victories, American universities institutionalize these new fields. Now many activists are mistakenly looking for evidence of transgenderism in the American and global past, posthumously transing masculine women like Joan of Arc, Anne Lister, and George Sand. While sex non-conforming people have been found throughout human history, transgenderism’s history is less than two decades old because is a concept fundamentally dependent on and spread by twentieth-century medical and digital technologies: cosmetic surgery, synthetic hormones, and the Internet.

Nevertheless, the past is still full of useful examples and rich lessons about human nature that we can use to understand our current era. I offer this essay as something that might encourage deeper and more critical thought about history’s relevance to our present moment. There have been other disruptive technologies that have intruded on our sense of our embodied humanity, deranging vulnerable young people in the past.

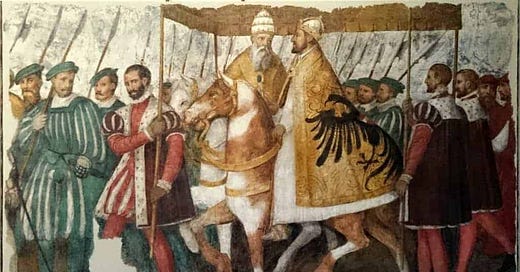

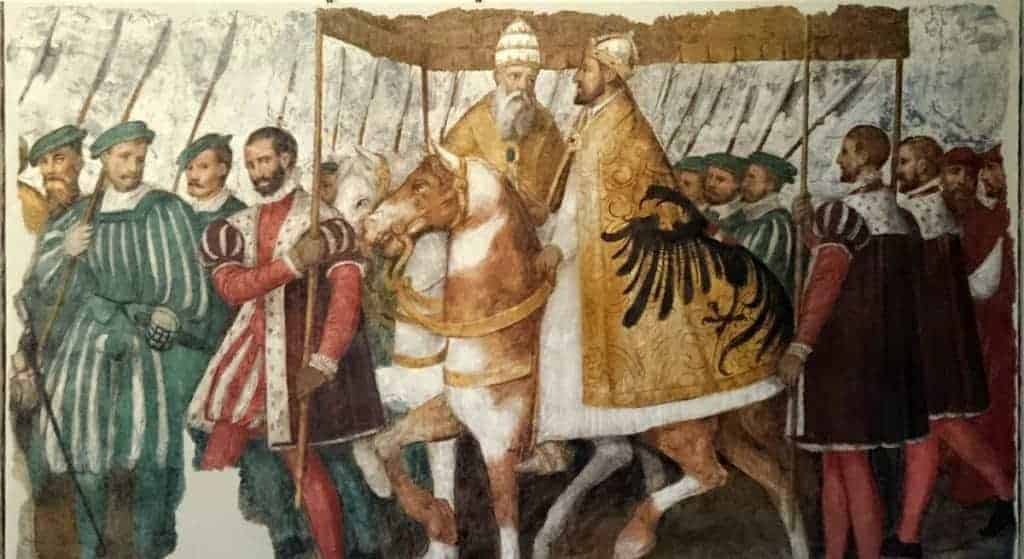

Once upon a time of fairy tales, murderous religious prejudice, and unspeakable cruelty—or the Renaissance, as historians call it—some men came to believe that parts of their bodies were made of glass, or sometimes, that their entire bodies were made of glass. Charles VI of France (1368-1422) is probably the most famous sufferer of what historians call the glass delusion. He came to believe that he was so refined and delicate that if struck or injured, his body would literally shatter into a thousand pieces. Delusions of fragility were not new in the Renaissance; sufferers in the classical and medieval eras imagined that their bodies were composed of earthenware before glass became the fashionable delusion.1 Advances in glass manufacture captured the European imagination in this era, and implanted desires for a new luxury product.

Glass itself was not a new technology, but technological advances in the manufacture of glass in the fifteenth century in Renaissance Venice turned glassmaking from an artisanal craft to an industry. Venetian glass became highly sought-after, and it became widely imitated throughout Europe. Venetian glass, with its transparency and purity, was associated with both luxury and fragility—so precious, yet so vulnerable.2 As Victoria Shepherd writes in her recent book on the history of human delusions, “the appeal of glass, a wondrous new material, as a metaphor for a person’s sense of themselves, is not difficult to understand in this context. To be made of glass is to be precious – rare, but fragile; it is an instruction to others to admire you, but not to get too close. There is something essentially magical, spectral about glass. . . . Glass perfectly symbolizes a sense of both supreme refinement and a nail-biting sense of vulnerability and contingency.”3

Charles VI was just the most eminent sufferer of the glass delusion. Stories of glass men spread throughout Europe. Literary historian Gill Speak notes that “the sheer volume of sixteenth-century accounts suggests that interest in the glass delusion had taken on epidemic proportions.” The most famous example is Miguel de Cervantes’ El licenciado Vidreira (The Glass Graduate, 1613), a story about a young man who suffered from the glass delusion after ingesting a love potion. Speak and other scholars credit Cervantes for spreading the notion of “Glass Men,” so that by the seventeenth century there were Glass Men throughout Europe. Notably, this delusion was associated with another diagnosis known as “scholar’s melancholy,” a kind of depression known only to the educational elite. This was a delusion suffered only by “men of letters, or members of the nobility, these Glass Men could have learnt of the delusion from earlier medical treatises, and from contemporary literary accounts accessible to them in the embryonic literary academies.”4 Specialized mystical knowledge was a component of this diagnosis—and no wonder. There are no known laborers or peasants who suffered from this delusion. They were required to use their bodies roughly and vigorously to make their way, and they had no money to pay tutors to make them literate, or servants to cushion them against the blows of life. The glass delusion was definitionally a luxury belief, or affliction.

The parallels between the glass delusion and the modern transgender contagion are obvious to any parents of middle school and high school students or their teachers today. Children are being encouraged to falsify their material reality and to embrace a delusion. Sometimes they are encouraged by false phantom “friends” online; sometimes by their schools and universities who have been told this is the next great fight for social justice. Frequently the internet and educational institutions work together to support this craze. These false identities are both transparent and fragile—we parents and teachers are told that these precious glass children will harm themselves if subjected to words or opinions they disagree with. We are told that it’s our duty to protect them against suicide by cushioning them against reality with language and medical procedures like cross-sex hormones and surgeries that will support their delusions.

Victoria Shepherd’s chapter on the glass delusion suggests other obvious connections to the transgender epidemic. For example, “The Glass Men frequently believed that they were being persecuted, and show a hypervigilance that looks a lot like paranoia. . . . Glass is a natural communicator of paranoia. A person made of glass can be seen into, and ‘read’.” She continues, “there are demands attached to a glass delusion, most urgently how the person with the delusion must be treated – with careful attention, care, respect. It’s never clear if the demands will be met. The signs are that in most cases they won’t be.”

She concludes with a nod to our modern digital panopticon and the anxieties it has provoked in many of us. “Glass is still resonant. Anxieties about fragility, transparency and personal space are more pertinent now to many people’s experience of living than they’ve ever been. It’s an elegant response to the society we have to navigate; a society that is increasingly crowded, in which modern technological advances isolate us but also offer apparently boundary-less communication. Glass delusion expresses social anxiety, which many of us experience to a lesser extent. It allows us to demand protection against drops and shocks, and transforms a lost soul like Charles VI into something worth treasuring and nurturing.”5 To be clear: Shepherd never makes the connection herself between the glass delusion and transgenderism. But can any parent or teacher read about these historical patients without thinking about their own trans-identified children or students?

Gill Speak also writes about the fear of being seen, and in a way that may offer a path forward for those of us working to reform our medical and educational institutions. He notes that another feature of the glass delusion is that “Glass Men” also suffered from photophobia, or the fear of sunlight. “The Glass Man’s fear of sunlight must have been connected with the notion that his body was, not fragile, but transparent, as the poet John Donne said: ‘Tismuch that Glasse should bee/ As all confessing, and through-shine as I’.”6 Fear of exposure, the fear of being seen for who one really is—of course this is terrifying to those trapped in delusions, either of glass or of a transgender identity.

It is an old cliché of journalism that “sunlight is the best disinfectant”—that is, that fact-finding and truth-telling are fundamentally healthy for the body politic. But light, transparency, clarity—yes, Enlightenment values—is the only way out of the darkness that has captured so many of us.

1 Gill Speak, “An Odd Kind of Melancholy: Reflections on the Glass Delusion in Europe, 1440-1680,” History of Psychiatry 1:2 (1990), 190-206; Speak, “El Licenciado Vidreira and the Glass Men of Early Modern Europe,” Modern Language Review 85:4 (October 1990), 850-865; quotation from 852. (Speak also published under the spelling “Spzak.”)

2 W. Patrick McCray, Glassmaking in Renaissance Venice: The Fragile Craft (Brookfield, VT: Ashgate, 1999).

3 Victoria Shepherd, A History of Delusions: The Glass King, a Substitute Husband and a Walking Corpse (London: Oneworld, 2022), esp. ch. 5, “The Glass Delusion of King Charles VI of France,” 159-85; quotation from 162.

4 Speak, “El Licenciado Vidreira,” 852. This story is also translated as “The Glass Lawyer,” or “The Glass Licentiate.” See also Or Hasson, “Between Clinical Writing and Storytelling: Alfonso de Santa Cruz and the Peculiar Case of the Man Who Thought He Was Made of Glass,” Hispanic Review 85:2 (2017), 155-72.

5 Shepherd, 184-85.

6 Speak, “Odd Kind of Melancholy,” 197-98.

Wow. Thanks for explaining this. I had no idea about this glass delusion. And holy smokes, what a delusion it was. I’m definitely going to look for Victoria’s book to learn more.

I’m the mom of an ROGD teen, and I’m often enraged, horrified and sad (as per my handle) about transgenderism and gender ideology. This gives me hope that someday people will look back on all this in utter disbelief. But what and how long will it take for that to finally happen?

As confusing and hard to understand how certain men of the 15th to 17th Century Europe could have imagined they were in part made of glass (I can't even wrap my head around it), so would it have been to these men of the Enlightenment as baffling, I suspect, to believe that some men are in actual and absolute truth women and some women are in the same truth men. Neither delusion makes any sense to this commoner except to say it is a contagious hoax employed by lost souls to give some meaning to their lives.