Psychologists are not legally required to affirm the gender identities of their patients

A psychotherapist who works with gender distressed young people without affirming their gender identities in California, where "conversion therapy" is banned, explains why her practice is legal

I am a licensed clinical psychologist in California who provides psychoanalytic psychotherapy to children, adolescents, and adults. Over the past few years, my practice has been dedicated to adolescents and young adults suffering from distress related to their sexed bodies and/or who identify as trans. I also treat individuals who have detransitioned, are considering detransitioning, or are confronted with the deeply painful dilemma of regretting having medically transitioned while remaining unable to detransition due to medical, financial, or other reasons. Additionally, I provide consultation and psychotherapy to parents of gender dysphoric and trans-identified youth. I collaborate with a network of mental health clinicians, medical providers (pediatricians, endocrinologists, gynecologists, etc.), legal specialists, multi-disciplinary researchers, bioethicists and others who share the common goal of ensuring compassionate, safe, evidence-based care to gender distressed and trans-identified youth.

I avoid having an online presence and therefore am writing pseudonymously for three reasons. Most importantly, many of these youth believe that anything other than immediate affirmation signals transphobia. Those who agree to see a therapist who publicly expresses concerns about gender identity ideology and medicalization are already capable of entertaining doubt. Those who might cling most desperately to their trans identity, who might go through their days with a sense of hypervigilance, are the very ones who are most in need of the consistent presence and attunement that therapy can offer. I do not want to make it any easier to be dismissed. Secondly, I have another job in addition to my private practice that requires me to not widely publicize my views. Lastly, I would rather not be harassed by activists.

When I have expressed my concerns about the gender-affirmative model, i.e., immediate affirmation and a quick push onto the medical pathway, under my own name, I have been accused—in print, on listservs, and in conversations—by those both inside and outside of my field of of being close-minded, bigoted, anti-trans, transphobic, threatened by gender non-conformity, and/or engaged in conversion therapy. I have been interrogated for organizing clinical training presentations by professionals in my field who have pointed out the potential harms of unquestioned affirmation followed by medicalization, discussed alternative ways of thinking about what we call gender dysphoria and how to treat it, and provided information about the state of the evidence base for social transition, puberty blockers, hormones, and surgery. I have also received statements of private support from many within my field who share my concerns but are afraid to express them for fear of encountering the difficulties described above. I am hardly alone in my experience. Most, if not all, of my like-minded colleagues who have publicly shared views that reject the dogmas of gender ideology and that point to the weak evidence base for medical interventions have received a combination of public vituperation and private support.

All of this is to say that I am acutely conscious of the enormous social and institutional pressure being placed on clinicians who resist the culture-wide push of the gender-affirmative model of care. I am pressed to the margins of my profession and constrained in my ability to make the case for what I believe to be best for my patients and for others with similar complexities involving sex and gender. My work goes on in the shadows amidst a carefully vetted network of parents and clinicians while the exponents of the affirmative model proselytize proudly and loudly. Despite all these difficulties, it is important to underscore that what I do is legal. Precisely because non-affirming therapists like myself often navigate minefields behind the scenes and bear an unjust stigma, with all the adversity that entails, it is crucial that we not succumb to certain temptations: to regard ourselves as rescuers or to exaggerate the extent of the persecution we ourselves face. We must not stretch the truth or make false assertions.

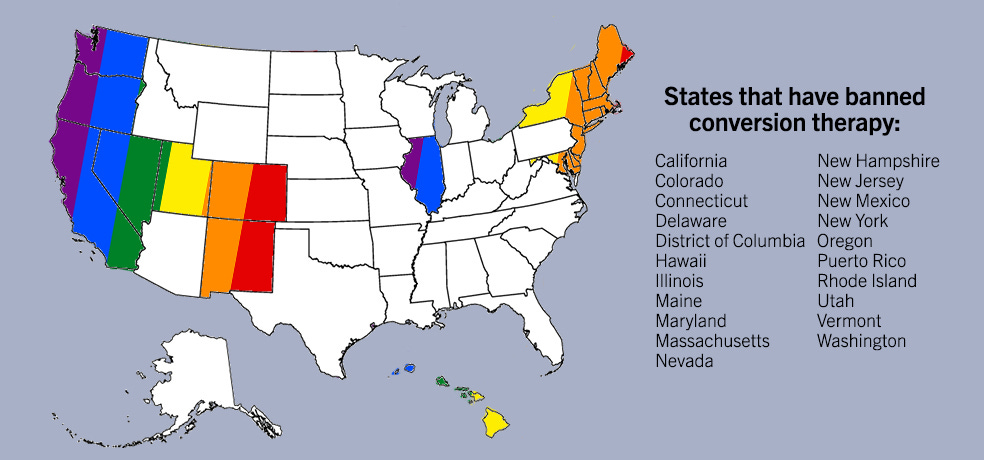

One claim that I have repeatedly come across is that in some states, such as California, therapists are required to affirm a patient’s self-reported gender identity or else risk losing their license on the basis of practicing conversion therapy.

This is false.

A close reading of the California law banning “conversion therapy” makes clear that no therapist is required to affirm a patient’s gender identity. Misguided assertions to the contrary instill fear in therapists and parents, unintentionally reinforcing the chilling effect that those who sought to include gender identity in definitions of conversion therapy intended to create. In order for therapists to practice therapy as usual–which is not gender-affirmative therapy– and for parents to feel safe agreeing to treatment for their minor or young adult child with such a therapist, we must not propagate these false claims ourselves.

In California, SB 1172 (approved by the Governor in 2012) is the pertinent legislative bill regarding sexual orientation change efforts, otherwise known as conversion or reparative therapy. It states:

This bill would prohibit a mental health provider, as defined, from engaging in sexual orientation change efforts, as defined, with a patient under 18 years of age. The bill would provide that any sexual orientation change efforts attempted on a patient under 18 years of age by a mental health provider shall be considered unprofessional conduct and shall subject the provider to discipline by the provider’s licensing entity.

Section 2, Article 15 declares:

(1) “Sexual orientation change efforts” means any practices by mental health providers that seek to change an individual’s sexual orientation. This includes efforts to change behaviors or gender expressions, or to eliminate or reduce sexual or romantic attractions or feelings toward individuals of the same sex.

(2) “Sexual orientation change efforts” does not include psychotherapies that: (A) provide acceptance, support, and understanding of clients or the facilitation of clients’ coping, social support, and identity exploration and development, including sexual orientation-neutral interventions to prevent or address unlawful conduct or unsafe sexual practices; and (B) do not seek to change sexual orientation.

“Gender expressions” is a vague term; based on the bill’s focus on same-sex sexual orientation, it is reasonable to presume that the term’s intended meaning is “expressions of gender non-conformity.” A definition clarifying the meaning would certainly be helpful, especially with respect to whether it encompasses identity as opposed to non-adherence to socially constructed male and female norms of appearance, behaviors, etc. However, let’s imagine that “sexual orientation change efforts” has been amended to “sexual orientation and gender identity change efforts.” It would still mean that mental health providers are prohibited from “efforts to change gender identity, that is to say, in the language of gender ideology, to intentionally change a trans individual into a cis one. In this hypothetical situation, if a therapist were to actively attempt to do this, such action could perhaps be argued to fit the definition of conversion therapy and be deemed illegal. Given a therapist’s task to remain as neutral as possible and to engage collaboratively in thoughtful reflection and exploration—not to tell patients who they are or what to do—active intent to change a patient’s self-declared gender identity would indeed be unethical if not illegal. It would also very likely be ineffective and counterproductive. Fortunately, this is not what non-affirming therapists do.

The American Psychological Association publishes standards and guidelines for practicing psychologists. Regarding the definition of “standards” and “guidelines,” they write:

As these terms are used in APA policy, “standards” include any criteria, protocols or specifications for conduct, performance, services or products in psychology or related areas, including recommended standards. Standards are considered to be mandatory and may be accompanied by an enforcement mechanism.

"Guidelines" include pronouncements, statements or declarations that suggest or recommend specific professional behavior, endeavor or conduct for psychologists or for individuals or organizations that work with psychologists. In contrast to standards, guidelines are aspirational in intent.

Guidelines are not legally binding. The APA’s “Guidelines for Psychological Practice With Transgender and Gender Nonconforming People” (2015) are, in their own words, “aspirational” and thus do not involve enforcement mechanisms. Moreover, their own guidelines caution against immediate affirmation:

Adolescents presenting with gender identity concerns bring their own set of unique challenges. This may include having a late-onset (i.e., postpubertal) presentation of gender nonconforming identification, with no history of gender role nonconformity or gender questioning in childhood (Edwards-Leeper & Spack, 2012). Complicating their clinical presentation, many gender-questioning adolescents also present with co- occurring psychological concerns, such as suicidal ideation, self-injurious behaviors (Liu & Mustanski, 2012; Mustanski, Garofalo, & Emerson, 2010), drug and alcohol use (Garofalo et al., 2006), and autism spectrum disorders (A. L. de Vries, Noens, Cohen- Kettenis, van Berckelaer-Onnes, & Doreleijers, 2010; Jones et al., 2012). Additionally, adolescents can become intensely focused on their immediate desires, resulting in outward displays of frustration and resentment when faced with any delay in receiving the medical treatment from which they feel they would benefit and to which they feel entitled (Angello, 2013; Edwards-Leeper & Spack, 2012). This intense focus on immediate needs may create challenges in assuring that adolescents are cognitively and emotionally able to make life-altering decisions to change their name or gender marker, begin hormone therapy (which may affect fertility), or pursue surgery. (pg. 842)

When working with adolescents, psychologists are encouraged to recognize that some TGNC adolescents will not have a strong history of childhood gender role non- conformity or gender dysphoria either by self-report or family observation (Edwards- Leeper & Spack, 2012). Some of these adolescents may have withheld their feelings of gender nonconformity out of a fear of rejection, confusion, conflating gender identity and sexual orientation, or a lack of awareness of the option to identify as TGNC. Parents of these adolescents may need additional assistance in understanding and supporting their youth, given that late-onset gender dysphoria and TGNC identification may come as a significant surprise. Moving more slowly and cautiously in these cases is often advisable (Edwards-Leeper & Spack, 2012). Given the possibility of adolescents’ intense focus on immediate desires and strong reactions to perceived delays or barriers, psychologists are encouraged to validate these concerns and the desire to move through the process quickly while also remaining thoughtful and deliberate in treatment. Adolescents and their families may need support in tolerating ambiguity and uncertainty with regard to gender identity and its development (Brill & Pepper, 2008). It is encouraged that care should be taken not to foreclose this process. (pg. 843)

The most recent WPATH guidelines for treating adolescents (SOC8, 2022) also recommend caution and explicitly acknowledge the possibility that a self-declared gender identity may change. Guideline 6.2 states:

We recommend health care professionals working with gender diverse adolescents facilitate the exploration and expression of gender openly and respectfully so that no one particular identity is favored […] Given [the great variation in individual identity development], there is no one particular pace, process, or out- come that can be predicted for an individual adolescent seeking gender-affirming care. (p. 550)

Guideline 6.3 states:

We recommend health care professionals working with gender diverse adolescents undertake a comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment of adolescents who present with gender identity-related concerns and seek medical/ surgical transition-related care, and that this be accomplished in a collaborative and supportive manner […] For example, a process of exploration over time might not result in the young person self-affirming or embodying a different gender in relation to their assigned sex at birth and would not involve the use of medical interventions (Arnoldussen et al., 2019). (p. 550-551)

As is written on the Department of Consumer Affairs California Board of Psychology’s website, “Anyone who thinks that a psychologist or psychological associate has acted illegally, irresponsibly, or unprofessionally may file a complaint with the Board of Psychology.” However, if the complaint relates to a particular treatment, it must be filed by the patient him- or herself, or in the case of a minor, the patient’s legal guardian: “The Authorization for Release of Client/Patient Record Information (Release) form is legally required for Board staff to obtain information from the psychologist about the treatment or evaluation you received. We are unable to investigate your complaint without a Release, and a psychologist cannot legally discuss your treatment without your written permission.” While I have heard of investigations by regulatory boards in other states into “unprofessional behavior” related to posts on social media, which are undoubtedly a terrible ordeal for these therapists and have a chilling effect, I am not aware of any decisions that have deemed such behavior a violation of the law or even of the guidelines. I am not aware of any therapists being investigated on the basis of practicing conversion therapy. If this were to occur, intent to change one’s gender identity would have to be proven, which is a nearly impossible task. A therapist who is practicing ethically and in accordance with the principles of psychotherapy will neither affirm nor negate a patient’s stated gender identity. A non-affirmative approach to gender distress that observes the standard protocols of the field will thus never violate such a ban or result in disciplinary action.

Parents who contact me seeking non-gender affirmative therapy for their adolescent or young adult child do so because they have been referred to me by a trusted source—either one of my colleagues or parents of current or former patients. They tell me they are seeking a therapist who will treat their children in all of their complexity and explore underlying factors and dynamics that may be contributing to distress with their sexed bodies and/or identification as trans. They express their concerns about medical intervention. I let them know that my approach is based on a careful exploration of all aspects of their child, a neutral stance towards their stated gender identity, and that I do not provide letters of recommendation for medical interventions due to what the independent systematic evidence reviews have determined: the quality of evidence for the potential benefits of puberty blockers and hormones is “low” or “very low” and such potential benefits do not outweigh the risks.

Some people equate trans-identification with delusional thinking. This doesn’t strike me as quite right: delusions are typically defined as fixed, idiosyncratic beliefs that are incongruent with culturally shared beliefs. Our culture has come to create, sustain, and celebrate the belief in gender identity and the notion of “being” as opposed to “identifying as” trans, which sets such beliefs apart from those held by people suffering from psychotic disorders. We could think of what’s happening as a mass delusion, but at what point does a mass delusion become a culturally accepted phenomenon? What is considered a delusion in one culture may not be viewed as such in another. As Suzanne O’Sullivan wrote in her book about psychosomatic illnesses, The Sleeping Beauties and Other Stories of Mystery Illness, “The unconscious embodiment of cultural models of distress gives people the means to act out conflict and to ask for help in a way that will attract the right sort of support, the sort that is free of judgment and stigma” (p. 71). Trans identification, and even the felt experience of distress with one’s sexed body, can be the socially and culturally mediated vehicle through which an unconscious bid for help with psychic pain is communicated.

Broadly speaking, the task of a therapist is to alleviate suffering as much as is possible. After all, there is no life devoid of pain. And though delusions, especially persecutory ones, may cause suffering, they also serve to protect against deeper, more painful mental and emotional states. Whether one believes he is being followed, is on the verge of discovering the key to life’s ultimate mystery, or is literally the opposite sex, such beliefs serve an organizing function: a way of staving off life’s intolerable, often shapeless terrors. We all need our defenses. Depending on our experiences, we learn to use different ones in various ways with more or less flexibility.

People must hold onto their delusions until they have something else that sufficiently organizes their internal world. A broader repertoire of ways to protect against pain is needed so that the more extreme and rigid ones that exacerbate distress move to the background or fall away entirely. Delusions are not treated by confronting them head on. Similarly, therapists are sometimes confronted with an unshakable belief that one is trans, rather than that one identifies as trans in a way that acknowledges the reality of sex, or the insistence that long-term, life-changing decisions can be made when the faculties and experience to make such decisions are absent. We cannot—and should not—attempt to change this belief, but rather to work on creating and sustaining a relationship that facilitates the development of internal scaffolding, of a capacity to think and feel as fully as possible without collapse.

My work with gender-distressed and trans-identified youth is not any different from my work with anyone else. That is to say that there is a specificity and singularity to every relationship I have with my patients. Deep and lasting change happens over time through the relationship more so than by any particular thing that is said or discrete insight that is discovered. My task is to attend to what the patient says and does not say, how she relates to me, how I relate to her, what thoughts, feelings, sensations, associations are stirred in my patient, in me, and between the two of us, and what we can learn through these experiences. I do my best to attune to my patient’s needs, desires, and limits; to change tack when I see fit; to survive frustration and anger directed at me without retaliation; to show sincere curiosity about their lives, what they’re thinking about, how they’re feeling, what interests them, why do they like this but not that, what are they yearning for, expecting, fearing; what makes them laugh, cry, scream, want to run away, come close? I can only think about one’s gender identity in the larger, nuanced, and complex landscape of my patients’ particular lives. Through collaborative exploration, we learn about ourselves; through a relationship that is co-created, we learn to experience ourselves and others in new ways. Through this process, some of my patients have desisted from identifying as trans. Some haven’t. Some may still, some may not. I do my best to invite and participate in sense-making, curiosity, engagement, contact, a sense of belonging and aliveness. What happens as a result is beyond my control.

“Similarly, therapists are sometimes confronted with an unshakable belief that one is trans, rather than that one identifies as trans in a way that acknowledges the reality of sex, or the insistence that long-term, life-changing decisions can be made when the faculties and experience to make such decisions are absent. We cannot—and should not—attempt to change this belief, but rather to work on creating and sustaining a relationship that facilitates the development of internal scaffolding, of a capacity to think and feel as fully as possible without collapse.”

This passage resonated with me deeply, even if it also frustrated me.

The best, most effective therapy takes time and trust. If patients have access to those things--if clinicians have access to them--there is great potential for help and change.

But so many current trans-identified or trans-questioning youth don’t even have a therapist--let alone a *good* therapist, let again alone the years of time to build a trusting relationship where the clinician can help them work through these issues in the appropriate way.

I am heartened to read about one such therapist’s work. I also see so much sober truth in their observations.

It does, though, seem in tension with the situation on the ground, so to speak.

Tough business: lots of minefields and fanatics who don't take prisoners. Good luck to you and others like you who take charge and courageously try to help these people deal with their problems.

Danny Huckabee