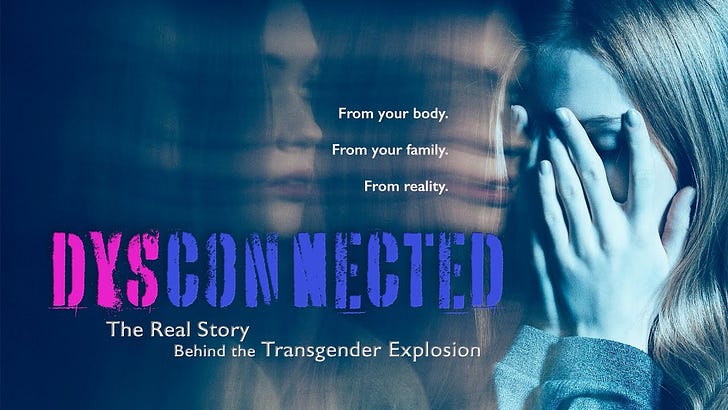

The documentary Dysconnected begins with the image of a young person in the midst of a solitary rapture. The young person is alone in a teenager's bedroom, addressing a webcam, speaking to networked multitude of potentially infinite size that the Internet has granted every one of its users the means to seek and the most engaging of its users the means to obtain. Anyone who has watched testimonials of religious conversion will recognize the ecstatic mood that suffuses the young person's affect, which seems bathed in an inner radiance of its own generation:

"Any doubts that I had any, you know, second thoughts any, like what ifs they're like what if you know what if I don't like my scars what if it feels inauthentic all of those worries are just are just gone. All I see in my future is hope right now and I know obviously I’ll have struggles but like right now it's like I just gained like 1000 more reasons to live and it's so huge and I didn't think that I would be this elated but like I'm so proud of myself for doing this I am so proud of my chest and I like I just can't wait to live my life."

The young person is referring to "top surgery," the recently-coined euphemism referring to the cutting off of the breasts of transgender-identified people to more closely match their physical form to their internal sense of "gender identity." Here I will cease the use of the gender neutral form of reference deployed above and begin to use the pronoun that the young person was assigned at birth and which she would -- the very next scene discloses this -- resume using two years later. (Cut to title card: "2 Years Later." "So here's the deal. I'm detransitioning") The speaker is a woman named Daisy Strongin, once a trans vlogger, now a detrans vlogger.

In the opening scene of Dysconnected, Strongin confesses to her doubts (“what if I don’t like my scars?”) in the course of avowing the ultimate renewal of her faith once the great act has been undertaken. She has staked her sense of well-being on a faith into which others on the Internet had inculcated her: on the faith that cutting off her breasts was not an act of medically assisted self-harm directed at her own sexed corporeality and its often cruel entailments, (the pain and mess of monthly menstruation, the susceptibility to pregnancy and its attendant risks, the reduction of one's complex selfhood to an object of predatory sexual desire) but rather a form of self-affirmation of the person she really was, the attainment of which would banish all the pains and insecurities that had once alienated her self from herself. Through an act of sacrifice of the flesh, she would become one with her true self, with the internal subjective sense of being a man, woman, both or neither, that determines her -- and our -- "gender identity." Through an act of amputation, she would make herself whole.

In its opening scenes, the filmmaker avails himself of a signal fact of the Internet age -- that the sociogenic identities spread by online contagion exist by, through, and for the medium in which they are disseminated, (indeed, they scarcely have an existence independent of that medium) and thus are exhaustively documented over time by their makers, with ever-increasing fidelity as our devices improve, often more thoroughly than any such process involving a third party could ever achieve. In a brief montage, we hear the effects of testosterone on Daisy's voice, which expands her vocal chords without also expanding the surrounding apparatus that supports the vocal chords, deepening the voice but imposing a slightly uncanny helium-like timbre onto it. We see Daisy's face and body subtly resculpted by the effects of testosterone and we see her come to resemble someone that many would reflexively refer to by the male pronoun that Daisy had adopted.

This of course is one of the primary motives for youthful transition: those who transition ealier, before the physical effects of natal hormones have locked in a male or female appearance are more likely to "pass" and thus to live as their chosen gender identity with a relative minimum of the fear of being "misgendered" that haunts many cross-gendered identified people. Daisy Strongin is a particularly useful case study for this reason: once an attractive young white girl raised in what the camera suggests is upper-middle class suburban affluence, she avails herself of the costly hormonal and surgical care available only to those able to afford it, and passes reasonably well as the cute young guy she dreamed of becoming in the age of affirmation. Her detransition is thus not a function of an inability to pass or be desirable in her new identity (as many detractors of detransitioners insist must be the case) but rather of an inability to persist in untruth.

The vloggers are nodes in a larger memetic process summoning new realities into being through the collective work of posting, which is a kind of total process of worldmaking that dissolves the boundary between reality and fantasy, and dissolves the discrete, freestanding work of art into an online heteroglossia that is the only form of cultural existence that many young people now know. This collective manufacture of ecstatic new realities with webcams and social media apps is a phenomenon to which those from the older established faiths will --or ought -- to be especially sensitive and attentive, for it is the technologically mediated successor to their own worldmaking practice. If they are to distinguish themselves from -- and establish their own superiority to this culturally generative practice, they must find persuasive grounds to do so.

The filmmaker is a believing and practicing Christian and thus is both intimately familiar with the rituals and rhetoric of conversion and therefore acutely sensitive to the religious dimension of the transgender movement as a rival faith. Indeed it is one that has obtained hegemony within a Western world that once identified as Christian. This is the central problematic of the work. He treats transgenderism as a form of heretical religion -- the latest iteration of a foundational heresy from which it springs -- that has risen to dominate what he regards as the one true faith. Much that is otherwise inexplicable about transgenderism's uncanny power to capture Western institutions becomes explicable when seen through this lens. Though I am not a practicing or believing Christian, I found this work, which is at base a work of Christian apologia centered on a topical theme to be compelling for reasons worth exploring in depth in later installments of this review.

There is much that could be said about this. 1) All gnosticisms have a religious ideal structure, and are cultic in ways in which we have of-late become familiar. The decay of our present technological civilization and its disorientations have re-opened "the religious question," which the Hebrews, Greeks, Hindus, Christians and all traditional cultures have affirmed as being coeval with being human - as part of the structure of all persons. It was no accident that Karl Marx wrote against this, and hope that the question of origins/destiny would be forgotten. Gnosticisms appeal to this question, but are not religions - though they may try to gain that status, attach themselves to religions, or replace them. People - especially young people who are thown into "fluidity," are desperate, and this is pretty much all our "culture" (which is itself hardly more than an ongoing adaptation to technology) has to "offer" - i.e. is capable (has the internal resources for) offering.

Well, every religion is a cult; this is no different, and every story of the great spiritual crises that led well-known converts to plunge themselves into the ecstasy of rebirth into a new being sounds exactly like this. Every story begins with what's clearly a terrible struggle with depression and anxiety, sometimes of great loss, and the new-found faith is the drug that alleviates all anguish.

Among the parts of this tragedy is the failure of parents like Daisy's to say *no.* We will pay for any therapy but not to have your body reconstructed into a new form. If the only available therapy insists on the next step towards consecration--well, parents have had to fight for their children's best interests against the medical profession before.

I appreciate your work and I especially appreciate the qualiity of your thought and writing; that's often greatly lacking from others.