In the Cathedral of the Multi-Faith Chaplaincy and Dean of Student's Office

Where Visions are Broadened

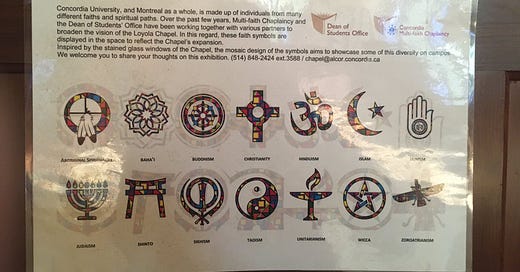

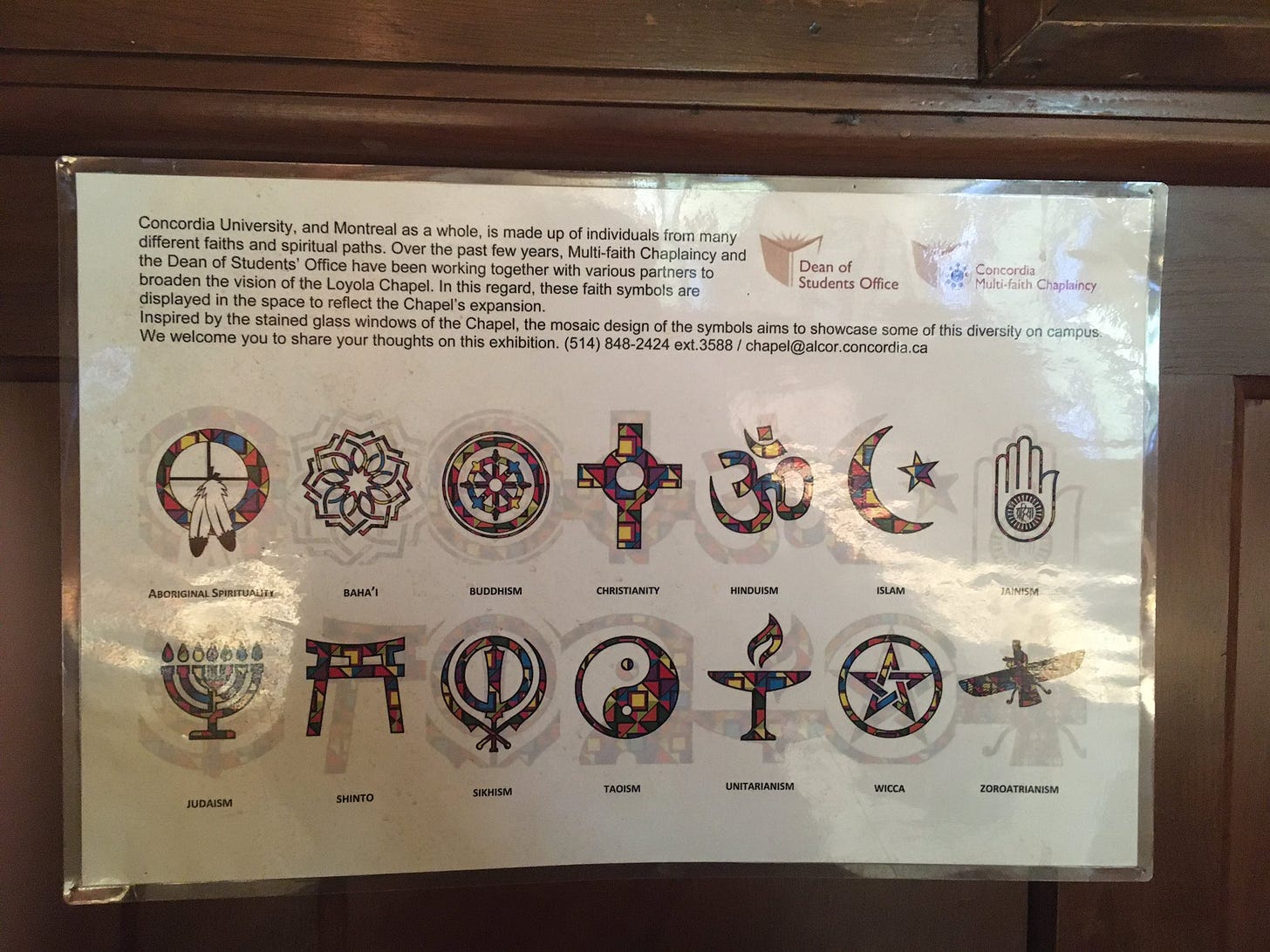

The mighty cathedral at the Loyola campus of Concordia University in Montreal has been converted into an ecumenical spiritual observance site with symbols from Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Jainism, Shinto, Taoism, “Aboriginal Spiritualism”, Baha’i, Christianity, Unitarianism, and Zoroastrianism hanging from the walls amidst the stained glass. It must be one of many such sites of Christian worship across North America and Europe where interfaith dialogue evanesces into the final triumph of tolerance as an end in itself. Unlike the great Orthodox Cathedral Hagia Sophia, in which Islamic symbols have been superimposed atop the iconography of Christian faith, the cathedral at the Loyola campus of Concordia University in the neighborhood known as Notre-Dame-De-Grace was not captured in an imperial war. (After many decades designated as a museum by the secular Ataturk regime, Hagia Sophia resumed its status as a place of Islamic worship in June 2020.) The faith that once sustained it dwindled away of its own accord and canceled itself.

Before the pandemic shut down all the buildings, I used to wander over to the cathedral in the late afternoon as the sun filtered through the high windows and bask in the spiritual void conjured there by the Multi-faith Chaplaincy and Dean of Student’s Office. There I would revisit the recurring thoughts about the inert and cossetted nihilism attending the Terminal Boredom at the End of History which have become a kind of inverted religious observance for me. I chortle inwardly, conscious of something freeze-dried within that might once have been capable of feeling the loss.

Unlike Philip Larkin in Church-Going, who finds himself wandering into abandoned country churches fallen into picturesque ruin, I was in a clean and well-maintained space. “When churches will fall completely out of use/ What we shall turn them into?” he asks. Churches have of course not yet fallen completely out of use. But in that building one glimpsed what the new vanguard of the progressive consensus (the campus administrators, whose ambitions encompassed the world outside of that institution’s walls) intend for them, and for us: a banality so complete that it courts its own kind of grandeur. “And what remains when disbelief has gone?” he goes on to ask. “Not even disbelief” is what the multi-faith chaplaincy has managed to incarnate in that space.

Year Zero is an ongoing inquiry into the ideological fever that overtook the governing and chattering classes of America during the Trump years. Free and paid subscriptions are available. The best way to support my work is by taking out a paid subscription.

In the morning I would work at the library across the courtyard in a brutalist concrete building built in the 1970’s, aimlessly roaming through the stacks in exactly the way I did as an undergraduate at Rutgers University, reading in an unstructured way from the obscure books — for the library at the Loyola campus was where the no longer fashionable books were warehoused — that caught my eye: an essay by Cicero, a poem by Elizabeth Bishop, a passage from Machiavelli’s Discourses. I had moved to Montreal with my wife and infant daughter in 2015 to bring to its conclusion an ugly familial dispute into which I had found been dragged by my wife and by a residual sense of filial piety that I would not have believed had ever been conveyed to me in the first place before it wound up hijacking my life.

I did not know anyone in Montreal and found myself spending more time online. I began to use the Twitter account I had started in 2009 and left largely disused over the years. I would post mordant and self-lacerating asides, creating little eddies of my own brooding presence amidst the surrounding heteroglossia. I look back at this characteristic statement from 2015, made poignant by the reply it received, still persisting in the digital ether, from the now deceased novelist Jenny Diski:

Eventually I discovered that a student co-op above the cafeteria on the other side of the building, reachable by descending into an underground passageway full of cubicles where the music students practice, was serving a free vegan lunch every day. I began to line up and partake of the free meals along side the undergraduate students of Quebec. It was right around this time my friends started hearing ominous rumors about themselves then in circulation.

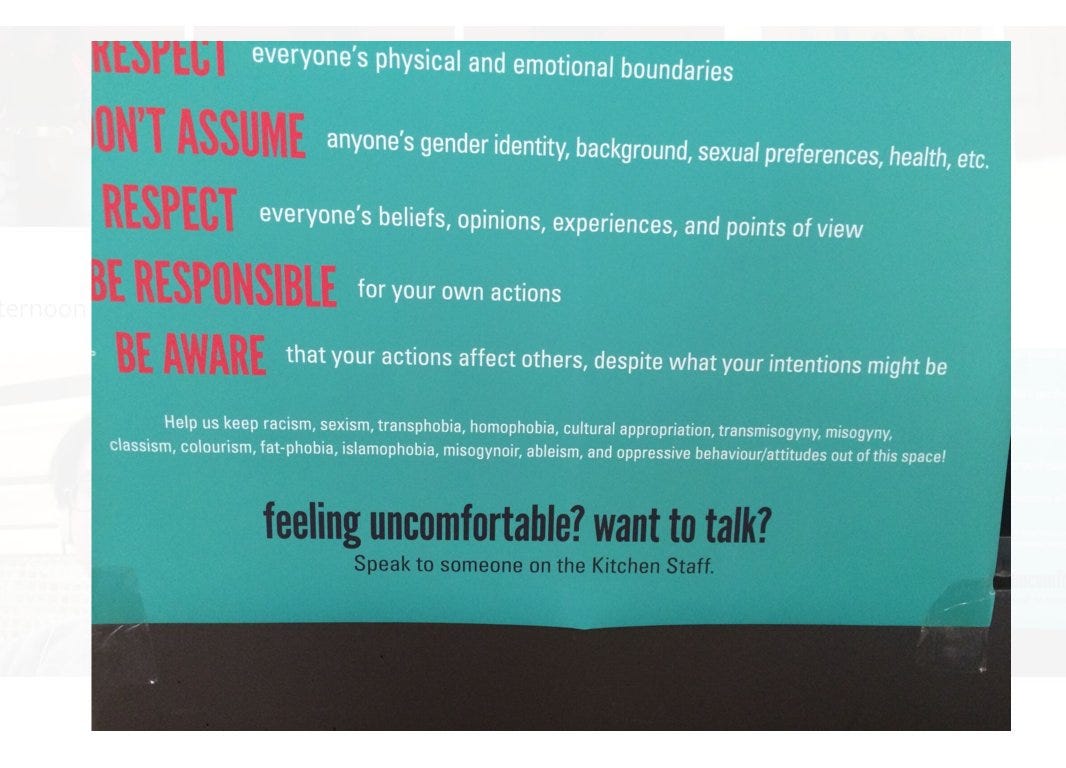

I used my first all-gender bathroom in the student co-op, adapting quickly to it. The family locker room at the indoor community pool had already habituated me to changing into swimming attire in front of mothers doing the same. It required little adjustment. And on the walls, I saw this remarkable document:

The most remarkable part of the document was its designation of the “Kitchen Staff” as competent to address one’s discomfort in the presence of “racism, sexism, transphobia, homophobia, cultural appropriation, transmisogyny, misogyny, classism, colourism, fat-phobia, islamophobia, misogynoir, ableism, and oppressive behaviour/ attitudes.” What were they going to do? It also seemed significant to me that “transmisogyny” preceded “misogyny”, just as “transphobia” preceded “homophobia” on the list of things to keep “out of this space”.

Here was a whole new way of thinking about the world, on the other side of “not even disbelief” — a new moral horizon and a new mandate to rule — manufactured by student life bureaucrats but embedded within the psyches and constituting the moral and emotional baseline of a rising generation of graduates. It did not have a name but it was plainly something other than the familiar creed of liberalism and tolerance which had razed the building site upon which the new foundation was then being constructed. On the one side of the campus we saw the work of demolition completed. On the other side, the new edifice was being built.

The Kitchen Staff will hear confession from 4-5 pm.

"a banality so complete that it courts its own kind of grandeur." is a beautiful description of the feeling which our new synthetic faith stirs up. The "coexist" bumper stickers that became popular about a decade ago would make me feel that way. The imagery of the old faiths might be included, but the resulting product is something in which nothing authentic about them survives.

Thank you for undertaking this project. It's young but already incredibly helpful.