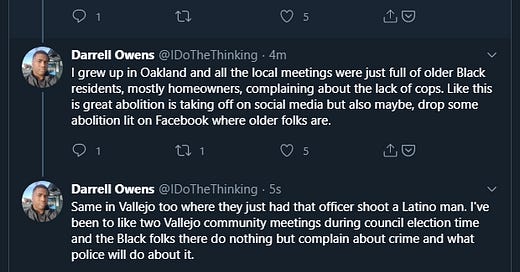

During the height of the summer of protest in 2020, when the prestige media and liberal institutions moved as one to embrace the rhetoric of defunding or abolishing the police, the policy analyst Darrell Owens tweeted a short thread that seemed to me more predictive of the near-term course of the movement than anything else in circulation at the time.

No one familiar with James Forman Jr.'s LOCKING UP OUR OWN, which recounts the central role that black politicians played in implementing the tough on crime policies that eventually yielded what would come to be known as "mass incarceration," will be surprised by Owens' anecdote. The politicians were responding to an overpowering demand from within the black community itself for the public good that precedes all others in priority as a duty of the state toward its citizens to provide. They were doing so in response to black communities being "devastated by historically unprecedented levels of crime and violence," that saw murders double and triple in Washington D.C. and many other large American cities.

The demand persists decades hence, even after the deleterious effects of what the new conventional wisdom has come to regard as a destructive overcorrection have manifested. Forman sets up the conundrum that his book seeks to investigate by noting that:

"In September 2014, the Sentencing Project issued a report comparing the attitudes of whites and blacks regarding crime and criminal justice policy. It found that when Americans were asked, “Do you think the courts in this area deal too harshly or not harshly enough with criminals?” more whites (73 percent) than blacks (64 percent) said “not harshly enough.” Media coverage of the report emphasized what the Sentencing Project called “the racial gap in punitiveness.”10 But the fact that almost two-thirds of blacks displayed such punitive attitudes received little notice. How could it be that even after forty years of tough-on-crime tactics, with their attendant toll on black America, 64 percent of African Americans still thought the courts were not harsh enough?"

Year Zero is an ongoing inquiry into the ideological fever that overtook the governing and chattering classes of America during the Trump years. Free and paid subscriptions are available. The best way to support my work is by taking out a paid subscription.

Owens was of course acknowledging the same overwhelming fact that served as predicate of Forman's book as it manifested in the course of his own activism. He was framing the issue as the intramural matter within the black community that it has been ever since the community obtained significant political power in the 1980's and 1990's -- and used it to pursue tough on crime policies within cities governed by Democrats in cooperation with the national Democratic party, which under President Bill Clinton, (working in tandem with then head of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Joseph Biden,) passed the landmark 1994 crime bill widely held to be a key contributor to mass incarceration.

He was moreover acknowledging that it was an issue on which a supermajority of the black community even today, having absorbed all the losses held to be inflicted by policing over the decades, continues to side with the forces of law and order. He was correctly postulating this intra-community resistance as the main obstacle to the attainment of the goal of abolition. Though he does not say it, the obstacle was overwhelmingly likely to prove decisive — as it has.

Forman's book, to which we will return in a later post, goes on to make a passionate case on behalf of a drastically less punitive criminal justice system and to portray those black officials -- Obama's former Attorney General Eric Holder prominent among them -- who played key roles in building the leviathan of mass incarceration as well-intended but fatally complicit in what he regards as the destructive system that he has made it his life's purpose to undo. He emphasizes that law and order was one of many things that a newly enfranchised black electorate sought from its newly empowered black political leadership -- but that it was the ratcheting up of a punitive criminal justice system — rather than the vast expansion in social welfare investments that were also sought — that turned out to be consistently achievable and achieved, to the detriment and sorrow of many within that community.

In setting the record straight, Forman reveals himself to be a reformer seeking transformative change who believes that telling the truth about the past and present, (rather than indulging expedient myths), is the best way toward the change he seeks. It is a conviction that makes Forman something of an outlier in a movement that has derived much of its popular influence (as well as its iron grip over progressive institutions) through the spread and sustenance of importunate falsehoods about police and prisons which in turn are leveraged on behalf of the thought terminating master narrative from which they issue.

Joining Forman in this conviction is the leading prison abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore. In an admiring profile published in the New York Times Magazine, the novelist Rachel Kushner quotes Gilmore debunking many of the myths about prisons that are articles of faith within the abolitionist movements, some of which have been put in circulation by her longtime collaborator, Angela Davis. Gilmore firmly rebuts the claims that either private prisons or a profit-seeking motive drove the rise of mass incarceration (92 percent of prisoners are held in publicly run institutions); that an absolute majority of the imprisoned are black (they are 33 percent of prisoners); and that the prisons are filled with nonviolent drug offenders (less than one in five are in prisons or jail for drug offenses, and the majority of those in jail or prison have been convicted of violent offenses).

In one vivid scene, Kushner compares and contrasts Gilmore favorably to Davis, describing the latter as charismatic by virtue of her "unflappable eloquence," while Gilmore put on display "a fierce and precise analysis," and noting that "it was Gilmore who commanded the room," and that in the course of rebutting one of Davis' claims, "a certain gulf opened between the women."

"Davis noted the “mistake,” as she put it, in the film “13th,” by Ava DuVernay, in sending a message that the main struggle should be against private prisons. But, she said to Gilmore, she saw the popular emphasis on privatization as useful in demonstrating the ways in which prisons are part of the global capitalist system."

It is this willingness to tolerate "mistakes" in the service of a cause when they prove "useful" that separates Davis and the many who take their cues from her from Gilmore and Forman, though they are all engaged in a common enterprise. (Forman is quoted in the same piece declaring himself a kind of prison “abolitionist”, though he takes care to define abolition as a distant horizon orienting action taken in the present.)

Gilmore goes on to express impatience with the idea that prison is a continuation of slavery by another means (an argument advanced in Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow and the documentary 13th).

"The reality of prison, and of black suffering, is just as harrowing as the myth of slave labor,” Gilmore says. “Why do we need that misconception to see the horror of it? Slaves were compelled to work in order to make profits for plantation owners. The business of slavery was cotton, sugar and rice. Prison,” Gilmore notes, “is a government institution. It is not a business and does not function on a profit motive. This may seem technical, but the technical distinction matters, because you can’t resist prisons by arguing against slavery if prisons don’t engage in slavery. "

These succinct and cool-headed debunkings of what Kushner calls "certain narratives people cling to that are not only false but that allow for policy positions aimed at minor or misdirected—rather than fundamental and meaningful—reforms" help Kushner to cast Gilmore as a practical visionary whose devotion to a transcendent proposition has withstood the rigors of empirical study.

Rigorous adherence to truth rather than expedient myth reveals the category mistake intrinsic to the movement. Pretending that our prisons are filled with non-violent drug offenders rather than violent criminals hides the trade-off between the welfare of the imprisoned and the community members they victimized en route to prison and may victimize again upon their release that any program to reduce their numbers by a significant amount must make. Comparing prisons to slavery frames the existence of these institutions as an urgent moral emergency that must be eradicated at any cost. The former claim says we need not strike a balance; the latter claim says that the very idea of striking a balance on such an issue would be odious and must not be entertained. Of course neither of these claims is true, and those who are directly exposed to the consequences of whatever trade-off we end up making know it better than anyone else.

They therefore end up in the curious position of being virtually the only bearers of an entirely commonsensical opinion that the progressive messaging apparatus has declared out of bounds who are thus authorized to speak: only in the aggregate, in response to pollsters. More detailed polling to tease out the nuances of the community’s attitudes, as this Vox piece puts it “broadly indicates that black people desire more community investment alternatives, more police transparency and accountability, and an end to police racism and brutality. In other words, they want a systemic, nuanced, and meliorating approach — not an either/or.” An entirely reasonable set of expectations light years away from the utopian fantasies that abolitionists indulge on their behalf.

In June 2020, the Princeton University sociologist Patrick Sharkey referred to “one of the most robust, most uncomfortable findings in criminology” — that “putting more officers on the street leads to less violent crime.” An entirely intuitive finding that few ordinary people would even think to pose as a question worthy of empirical study could only cause discomfort in a discursive community in which the made up claim to the contrary has attained the status of dogma through sheer repetition. Sharkey is engaged in a sales tactic called “pacing and leading” his imagined audience of abolitionists, in which he seeks to placate, soothe, and lead them back to reality, redirecting their energies toward achievable and empirically tested reforms. The potpourri of strategies he goes on to propose includes some reasonable and promising sounding measures that in the aggregate do not take us remotely near a world without police or prisons.

Democratic Party messaging at the national level abruptly turned in April of 2021 to promises of funding the police and audacious denials of ever having indulged the rhetoric. The viral meme grew explosively and then had to be reined in by a party that saw partisan disadvantage in its continuance. But the party did not merely bend to the weight of public opinion. It also saw the fundamental unworkability of the abolitionist temper that its nonprofit activist organizations have cultivated within its ranks which set the tone of the integrated messaging apparatus that dominated the passion play of 2020 and remains poised to do so for myriad other subjects that fall within the ambit of its grand narrative in the years to come. It will need to make similar calculations on successive fronts in the years to come.

Excellent post. I often wonder how much the bizarre (for lack of a better word) Democrat position on crime and prisons is due to trying to explain away the results of their other policies. When your party is A) in control of all but one or two major cities, B) has a death grip on education K-College, C) Needs the votes of older minorities living in those dysfunctional major cities, and D) your party is heavily funded by public employee unions... well, you've got a really awkward needle to thread. You have to blame something for crime and related social ills but all the proximate and plausible causes are your own programs and institutions. It is rather amazing that the Democratic coalition has held together as long as it has, all things considered.

Wesley, in your previous post ("The New Abolitionism") you wrote:

'Contemporary abolitionism shares a basic affective profile with the "general category of political vision" of its predecessor movement and shares it with a broad range of other contemporary movements that seek to alert the public to great moral emergencies ongoing in our midst... This "general category of political vision" does not, of course, coalesce into a Successor Ideology until it is married to another conceptual element, to which we will turn in the next post.'

Did you address that "[additional] conceptual element" here? Are you suggesting that it is the "Rigorous adherence to truth rather than expedient myth"? Or is it the the ongoing negotiation elites must navigate between ideas that "[grow] explosively... within [the] ranks" and their "fundamental unworkability" as practical political aims? Am I missing your point entirely? Or is it that you will address later the "conceptual element" to which you referred in the final sentence of the previous post?